Geology of the White Walls Way

As you walk the Whitewalls Way from Malmesbury to Luckington you will be walking entirely on rocks of the middle Jurassic period, laid down around 160-165 million years ago. At this time, the underlying rock of what was to form the Malmesbury district was a lot further south than it is now - about 30N, roughly the latitude the Canary Islands are today. It was part way through a long erratic journey north from near the South Pole, where it had been 330 million years earlier, borne by moving tectonic plates – a journey that continues today. The seas were warm with strong currents – similar to the modern Bahamas. This environment gives rise to ooliths, which are tiny egg-shaped bodies formed by precipitation of lime (calcium carbonate) on a minute nucleus of sand. Deposition of these in the sea, and compression by sediments deposited on top, has given rise to the rock (oolitic limestone), which underlies most of the area. However, the sediments being deposited in the Jurassic seas varied quite a lot from this general picture, and as this affects both what you will see on the walk and what you feel under your boots, a little more detail is called for.

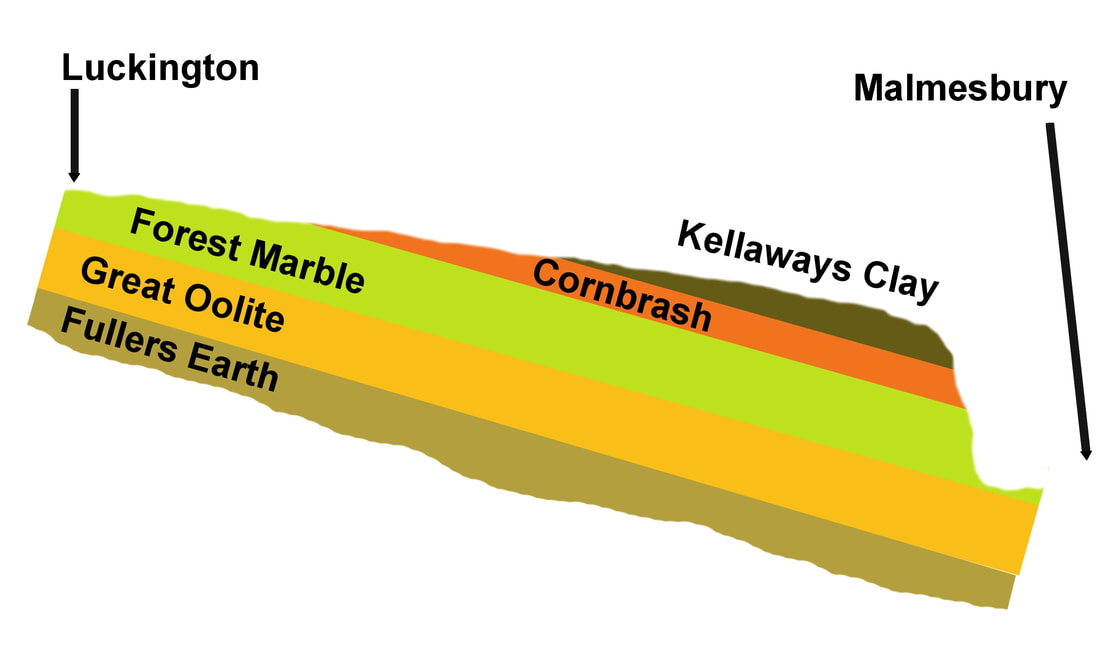

The sequence of rocks in the Whitewalls Way area is shown in the diagram below.

The sequence of rocks in the Whitewalls Way area is shown in the diagram below.

Figure 1: Rock Sequence in the Whitewalls Way Area

Fuller's Earth

The deposition of oolitic limestone in the Jurassic was interrupted by volcanic episodes which deposited minerals which turned into a thick layer of clay – the Fuller’s Earth. All traces of the volcano have vanished, but it must have been reasonably close – possibly in the western approaches to the English Channel. The Fullers Earth is not seen on this walk, but it outcrops close to Malmesbury and has had an effect on the development of the woollen industry here and throughout the Cotswolds, since the clay has the property of absorbing the grease from sheep’s wool – and was used for this purpose in the process known as fulling. The development of Malmesbury as a town thus owes something to this ancient volcano.

Great Oolite and Forest Marble

Once the volcanic episode was over, oolitic limestones continued to be deposited in our area and these are divided into two fairly distinct layers, known as the Great Oolite and the Forest Marble. The Great Oolite can be seen near Luckington and is an excellent building stone – the formation provided the stone for building much of Bath and the older Oxford colleges. The underlying rock for most of the walk is however the Forest Marble, and it is this that provided the building stone for most of the local villages. It is not strictly speaking a marble, but rather a hard limestone – it is named after Charnwood Forest in Oxfordshire where it was once used for making ornamental fireplaces.

The seas in which the Great Oolite and Forest Marble were deposited were inhabited by a variety of creatures, largely shellfish, and you can see some of these preserved as fossils. The most common fossil remains are shell debris, the remains of long-ago beaches and sandbanks. There were larger creatures in the seas of the time, but they stayed further out to sea where there was more to eat – hence their remains are not found here. On the adjacent land masses the dinosaurs held sway, including Megalosaurus, the first dinosaur to be named, whose remains have been found in rocks of the same age near Oxford. The first birds (now the only surviving relatives of the dinosaurs) were beginning to take to the air. The vegetation would have looked odd to our eyes – there were no flowering plants then, but there were swampy forests of such plants as conifers, cycads and the maidenhair fern tree Ginkgo. A specimen of this “living fossil” species, apparently unchanged since the Jurassic, is planted outside Sherston Post Office – a living link to the time when its ancestral relatives grew on the islands round about the present site of Sherston.

The seas in which the Great Oolite and Forest Marble were deposited were inhabited by a variety of creatures, largely shellfish, and you can see some of these preserved as fossils. The most common fossil remains are shell debris, the remains of long-ago beaches and sandbanks. There were larger creatures in the seas of the time, but they stayed further out to sea where there was more to eat – hence their remains are not found here. On the adjacent land masses the dinosaurs held sway, including Megalosaurus, the first dinosaur to be named, whose remains have been found in rocks of the same age near Oxford. The first birds (now the only surviving relatives of the dinosaurs) were beginning to take to the air. The vegetation would have looked odd to our eyes – there were no flowering plants then, but there were swampy forests of such plants as conifers, cycads and the maidenhair fern tree Ginkgo. A specimen of this “living fossil” species, apparently unchanged since the Jurassic, is planted outside Sherston Post Office – a living link to the time when its ancestral relatives grew on the islands round about the present site of Sherston.

Cornbrash

As the sea level began to rise in Jurassic times, the Forest Marble was succeeded by a very distinctive limestone called the Cornbrash which occurs widely over the Cotswolds. The Cornbrash has properties which made it suitable for growing corn in the days before modern agricultural machinery – as opposed to most of the Cotswolds which was sheep country. The relatively weak limestone had eroded into small pieces which did not impede the plough (“brash”) and there was enough clay to hold nutrients and water, but not so much as to promote waterlogging. The Cornbrash also provided a firm substrate for building – central Malmesbury is built on Cornbrash

Kellaways Clay

After the Cornbrash was deposited, the environment continued to change. Sea level rose further in our area, and although land was further away it started to have a greater influence, depositing organic-rich clays derived from the terrestrial environment. The first of these clay formations is the Kellaways Clay, and you will meet this as you walk out of and in to Malmesbury. Clay deposition went on throughout the Upper Jurassic for the next 10-15 million years, forming the Oxford and Kimmeridge Clays which are such a feature of the land to the east. These clays may have been deposited in the Malmesbury area also, as was a thick layer of chalk in the succeeding Cretaceous Period. All this has gone: eroded away in the succeeding 60 million years of the Tertiary Period when Britain once again rose above the sea

Naming of rocks

Incidentally, the names of these rocks were given in the late eighteenth century by William Smith, who is generally credited with making the World’s first national geological map and who started his researches in the Bath area. These are thus some of the World’s first geological names

The Cotswold dip-slope

The local rocks are not just a horizontal layer-cake. A legacy of the Tertiary Period is the approximately 3 NW-SE slope of the area, characteristic of the Cotswold dip slope. This slope reflects the slope of the underlying rocks, which were horizontal when laid down, and have therefore been tilted upwards by some massive force. This may have been caused by the uplift of the Alps far to the south, which was caused in turn by the collision of two tectonic plates. Because erosion has been faster on the higher parts of the Cotswolds, the younger rocks have eroded off more than round Malmesbury. The effect is thus that, when walking from Malmesbury to Luckington, you are walking back in geological time, as shown in Figure 2. The steep slope on the right of the diagram is the valley cut by the River Avon

Figure 2: Simplified geological Cross-Section along the Whitewalls Way from Malmesbury to Luckington. The tilt of the strata is highly exaggerated

Ice-age valleys

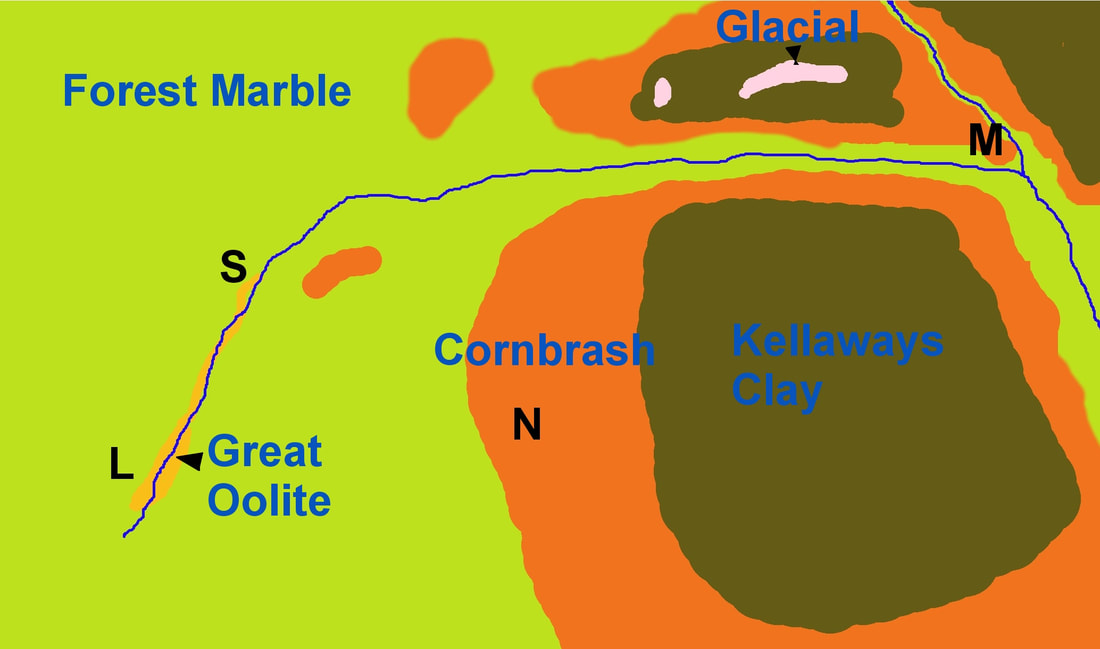

A striking feature of the area is the trench-like valleys which hold the River Avon and its tributaries. The modern river is not large enough to have cut them – almost certainly they largely date from the end of the last Ice Age, about 10,000 years ago. This lasted about 100,000 years, and a large icecap accumulated over most of Britain. Though the main icecap did not quite reach the Malmesbury area, the landscape would have been tundra-like, with accumulations of ice and snow on higher ground. We now know that at the end of the Ice Age the temperature rose remarkably quickly and this would have generated large volumes of meltwater, roaring down the existing valleys and excavating them close to their present depth. These events would have made the recent floods look rather pathetic. The excavated material was deposited on the plains beyond Malmesbury, or swept out to sea. Another legacy of this time is a range of superficial deposits on higher ground, probably from flowing meltwater, which are sometimes enough to change the properties of the soil which develops. Figure 3 shows a simplified geological map of the area. Note that there is a small area of Great Oolite in the valley between Sherston and Luckington. This is the “Sherston Inlier”- in which the Great Oolite appears at higher elevation than would be expected from the surrounding geology, for as yet unexplained reasons

Reduced gravity

If you feel a spring in step as you walk through Malmesbury, it could be because you weigh a little less than you do (say) on the plain near the Bristol Channel. Because Malmesbury is underlain by some relatively light rocks, the force of gravity is not quite so strong there as it is in places underlain by denser rocks. The effect is not large, though it is easily measurable by scientific instruments. If you weigh exactly 13 stone in Chipping Sodbury, you will weigh only 12 stone, 13lb and 15.974oz in Malmesbury. Or if you prefer metric units, if you weigh exactly 80 kg in Chipping Sodbury, you will weigh 79.999 kg in Malmesbury. The bad news is that by walking up to Luckington, you will put on 4 thousandths of an ounce. This extra weight will be dwarfed by that of the mud clinging to your boots

Figure 3: Simplified geological map of the White Walls Way area. Geological names in blue. M = Malmesbury; N = Norton; S = Sherston; L = Luckington

Measurements of the force of gravity are performed to try to infer what is underground without the expense of drilling boreholes. Another form of survey is the aeromagnetic survey, in which tiny variations in the Earth’s magnetic field are recorded from an aircraft. In our area, this revealed that about 10,000 feet below the surface between Sherston and Tetbury, there is a large body (several miles across) with magnetic properties. Although it is not known for certain what it is, its characteristics lead geologists to believe that it is the same rock as forms the Malvern Hills to the North. This is the oldest rock in southern England, dating to the late Precambrian period 660-680 million years ago.

I hope you have enjoyed this general account of the geology of the Whitewalls Way. You can find more details in the following references, and the website gives access to some geological notes on specific parts of the path.

I hope you have enjoyed this general account of the geology of the Whitewalls Way. You can find more details in the following references, and the website gives access to some geological notes on specific parts of the path.

Richard Skeffington

Professor of Physical Geography, University of Reading

Professor of Physical Geography, University of Reading

References

- British Geological Survey (1970) 1:50,000 Geological Map of the Malmesbury District, Solid and Drift, Map E251. Available from bgs.ac.uk.

- Cave, R., ed. (1977). Geology of the Malmesbury District. British Geological Survey Memoir, BGS, Keyworth, UK. Available from bgs.ac.uk.

For a beautifully-illustrated general account of the geology of Britain, see:

- Toghill, P. (2000) The Geology of Britain: an Introduction. Airlife Publishing, Marlborough.

And for a lead into academic research, see:

- Brenchley, P.J. and Rawson, P. F.,eds, (2006). The Geology of England and Wales. The Geological Society, London.

In this book, our area is covered by:

- Cope, J. C. W. (2006) Jurassic: the Returning Seas In: Brenchley, P.J. and Rawson, P. F., eds, (2006). The Geology of England and Wales. The Geological Society, London, pp. 325-363.

The stream support scheme, and the mainly positive effects it has had on the aquatic vegetation, are discussed in:

- Haley, M. A. (2009) The impact of stream support on the hydrology and macrophytes of the upper Bristol Avon Bioscience Horizons> 2: 44-54 doi:10.1093/biohorizons/hzp009. (See biohorizons.oxfordjournals.org). (Bioscience Horizons is a journal that publishes high quality undergraduate projects, from Bath Spa University in this case).

The discussion of Hancock’s Well, Luckington, contains a quotation from John Aubrey in:

- Jackson, J. E. (1862). Wiltshire: the topographical collections of John Aubrey FRS, AD 1659-70. Devizes: Henry Bull. See history.wiltshire.gov.uk

About us

The White Walls Way has been developed by Malmesbury Area Pathfinders (MAP), with funding from the Steve Cox Mayoral Fund, Malmesbury Carnival, and Wiltshire Council's Malmesbury Area Board. MAP is a community group dedicated to promoting walking in North-West Wiltshire.

MAP is part of MVCAP, a registered community charity (Reg: 1155592) based in Malmesbury, Wiltshire, UK.

(c) 2021 MVCAP

MAP is part of MVCAP, a registered community charity (Reg: 1155592) based in Malmesbury, Wiltshire, UK.

(c) 2021 MVCAP